Scared to Death: 1970's Public Information & The Child

Do Look Now: ‘Every Parent’s Worst Nightmare’ – (Un)charted Water, Unsupervised Play and The Drowning Child

A clanking 16mm projector, a freezing cold parquet floor, ominously dimmed lights and perhaps even a uniformed policeman striding purposefully into the school hall. The inevitable augers of that most traumatizing of school experiences: the screening of a Public Information Film. These crackling, washed-out warnings about the dangers of railway lines, busy roads and stagnant ponds became part of the fabric of our everyday 1970s unsettlement, and The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water joined the ever-increasing roster of nightmarish specters seemingly queuing at the bottom of our beds on a ghoulish rota. (Fischer 2023).

Released in 1973 Lonely Water was a mimetic slab of Hammer-horror-meets-New-Hollywood, it was the harbinger for a new kind of public information film that would lean into the generic conventions of horror. Designed to shock and terrify children into playing safe. A short public information film with a running time of 1 minute and 29 seconds, it depicted to children something that was seldom shown to adults: the perished and drowning youth; the dying and soon-to-be-dead child. Directed by Jeff Grant, Lonely Water represented a radical reorientation in the content of the public information films, redrawing the boundaries of what could be depicted by a public broadcast. “With the relaxation of censorship laws in the early 1970s”, writes McGahan “more explicit images reached our screens... [giving way] to harder-hitting safety warnings. A succession of blood-curdling mini-horrors were transmitted as COI safety campaigns attempted to shock increasingly jaded audiences out of their complacency”. An aesthetic turn that mixed stark and foreboding narrative devices with an unfettered graphic palate of disturbing images, Patrick Russell describes these public information films as having “a sort of surreal shock therapy”.

Before an analysis of Grant’s film, it is important understand the concomitant conditions whereby films produced by a public body aimed at children could oscillate from the likes of Teenagers Learn to Swim and Charley Says to Lonely Water, Apaches (1977) and The Finishing Line (1977). A harbinger for a public information film, Lonely Water grew out of a composite shift in cultural typology, which derived across the pond as the optimistic post-war love-in of the 1960s America came to a sharp dark end. Announcing themselves out of this traumatic manacle was a transgressive generation of 1970s filmmakers – unshackled and disavowing, technologically and formally free working in a rapidly developed field – and their works would transpose on screen the feeling that occupied the decade: apprehension. Both abstracted and laid bare, unspeakable fears and taboos were depicted cinematically in what Julian Petley and Xavier Mendick term the “Shocking Cinema of the ‘70s” (2022). Atop the litany of perversions, phobias and fears brought to life on celluloid in the 1970s: the transgression of child(hood). The accident prone, hurt and trespassed, absent, missing, gone-too-soon children; those who disaster strikes down. The (un)dead, dying child. When this is represented onscreen, Emma Wilson argues that it:

enables films to mobilise questions about the protection and innocence of childhood, about parenthood and the family, about the past (as childhood is construed in retrospect as nostalgic space of safety) and about the future (as fears of for children reflect anxiety about the inheritance left to future generations (2).

In his sociological study, Joel Best’s Threatened Children: Rhetoric and Concern about Child-Victim (1990), traces the then emergent and always-contemporaneous topic of the child victim and how the occurrence of this subject played out in American culture and society. In the work Best argues that the “wave of public concern over threats to children... spread during the 1970s through campaigns against sexual abuse, adolescent prostitution, child pornography and child snatching, and peaked with the missing child movement” (176). What Best traces is reflected in the films from the time, augmenting Wilson’s notion of the child subject as refracted and reactive site within films.

Reified together on screen in the landscape of US cinema and the New Hollywood movement of the 1970s, it further evidences the mobility of the child as a go-between for life and art. In the most memorable movies of the period, the subject of the transgressed child is repeated and reformulated over and over. Some notable examples include Paul Schrader's Hardcore (1979), Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976), Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976), Richard Donner’s The Omen (1976), Terrence Malik’s Badlands (1973), Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). And of course, William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), marketed as ‘the scariest film of all time’, testament to the fact that the troubled-child-in-trouble located within the horror genre is the natural site for the provocation of spectatorship fear: “it’s generative dialogue with the idea of the uncanny child as both subject and object of terror” (Lebau 168)

And so, with a formal deviation from the classical narrative norms (taking cues from stands of classical the Hollywood, contemporary European and Asian cinema) - a new filmic lexicon announced itself. A clean break that opened the language of cinema. One of the key points identified as a governing characteristic of this new movement in Todd Berliner’s Hollywood Incoherent: Narration in Seventies Cinema, a point which holds relevance for the topic at hand, is how “[s]eventies films prompt spectator responses more uncertain and discomforting” (52). And so, while cultural osmosis is certainly a hard thing trace, I would argue that there must have been some cross Atlantic influence, if not in formalism and style, but at the very least in characteristic(s) and in the congruence of the child subject in British filmmaker Nichoals Roeg’s 1973, Don’t Look Now.

To this day, Don’t Look Now, remains the emblematic representation of every parent’s worst nightmare. Perhaps the ultimate encapsulation of the transgressed child: horror, tragedy, loss and guilt are bound up with the figure of the drowned-dead child which is in turn “bound up with aesthetic of the film, its return to shapes and liquid forms, seepage and bleeding colour” (Wilson 11). And while the plot of the film in some regards can read an interior odyssey into the mesmeric horror of parental grief: an experience and journey rendered with a cognition of mournful dislocation, horror and the supernatural. This analysis is concerned perhaps with the works most terrifying sequence: an incident from the banal every day. The opening sequence: the unsupervised child around water . A notion which is imbued with more fear and is more horrifying than any devil possessed child; a fear much more primordial, instinctually rooted in the condition of natural occurrence. Guaranteed by its composite reality, made of bricks and mortar: the mundane, the simple, the incidental. An accident which can envelope the child in a matter of seconds with utter incongruence.

Indeed, there is fatalistic sensibility as the children play by the pond, with the numinous watery elementalism seeping into the picture. As they play outside in in the rain, their mother Laura Baxter (Julie Christie) portentously searches through her books to find an answer to a question her daughter asked her: if the earth is round, then why are lakes flat? A sense of dread that, writes Matthew Jackson:

fills every crack and crevice like water, which brings us back to the film’s use of symbolism, and what it really achieves. Water flows into any opening it’s allowed, fills any vessel it enters to that vessel’s exact shape. It’s continuous, but it’s also mercurial, boundless, able to spread in all directions, able to take just about anything with it along the way. That sense of water’s power, coupled with Roeg’s effort to give us the sense of prophecy and doom layered over the narrative, creates the feeling that time in the film is like water, shapeless and flowing and able to fill any void.

In many ways, the opening sequence of Don’t Look Now, in which an unsupervised young girl playing outside drowns whilst her parents are busy bickering inside, plays as the perfect public information film. Addresses in stark imagery one of the prominent anxieties of parent's fears tied up with the child and water, as well as their own responsibility as all-pervasive-safety-nets. Capturing one of the longstanding fixtures in COI safety concerns around children and watery places. Indeed, as Mark Sanderson elucidates:

The opening sequence of Don’t Look Now, which includes the titles, contains more than one hundred shots but lasts just seven minutes. It is a textbook example of compression and encapsulation, giving the unwitting viewer the whole ensuring film in a nutshell. It also serves as a warning: blink and you’ll miss it: In other words, keep your eyes peeled. Do Look Now. (33)

It influenced and anticipated the aesthetic turn of the public information film in terms of style, brevity and economy: “a devastating sequence, its impact increased for being so compact. Roeg has thrown a rock into the pond and the rest of film simply watches the ripples spread out” (ibid, 41). And the ripples seeped out of the film irrecoverably: the drowned child in the red jacket transmogrifying into a form of suspended reality – Little Red Riding Hood disappeared under the deluge. With the spectre and spectacle of this impossible finality formalised, frozen in still time and configured on-screen, it announced an emotional latitude for filmmakers dealing the child subject. Indeed, the mise-en-scenè of Don’t Look Now’s drowned child would affect, inform and transform the composite constitution of the public information films that were concerned with water, the child and unsupervised play. Not only was its leakage evidenced mimetically in visual terms – formalism, frame, atmosphere, and aesthetics – but it also signalled the shifting barometers and unbounding of taboo around the representation the child in visual media.

Returning then, to Grant’s Lonely Water, made in the same year as Don’t Look Now (a correlative in both temporal proximity and unsettling content of the drowning child) it was commissioned following pressure from the Royal Society for Prevention of Accidents to reduce the number of fatal accidents of children in and around water. To combat the rising number of child deaths in the 1970s, the COI changed tact from its humorous Watch with Mother parental address and animation style to stark and unsettling content. The goal: to shock children out of their complacency; to “mobilize fear and anxiety to promote safety and security” (Burke 193). At a concise 90-seconds, Lonely Water was primarily designed for child audiences, airing during ad-breaks between children’s television programming and school holidays.

With Donald Pleasance providing an ominously creep voice over – a narration which is macabrely sardonic with the tone shifting between nonchalance, glee and urgency – as ‘The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water’. This hooded figure is a wraithish reaper of death who stalks children as they play near rivers, ponds and watery waste grounds. The Spirit compelling watches over children as they engage in the kind of reckless and imprudent behaviour that results in drowning. Markedly a terrifying spectacle, Lonely Water is not only traumatically discomforting in showing children perishing in water, but also a perverse one given that the Spirit narrator takes “pleasure in the deaths he both witnesses and seemingly orchestrates” (ibid).

Such a dramatic shift in the COI’s approach did not go unnoticed by the film’s director. When the script came across his desk, Jeff Grant wrote: “I read it and got a bit of a shock”. Nevertheless, Grant was “impressed and intrigued”, already familiar with the form(at) he understood rationale of this controversial change in direction:

It was designed to warn of the dangers of playing by stretches of water such as disused gravel pits etc. where there were likely to be underwater hazards. Gone was the gentle cajoling of Rolf Harris who had recently appeared in a public information film aimed at persuading children to learn to swim. This one plumbed the darkness; it set out to scare... I had never seen a script for a ‘filler’ which in my opinion hit where it hurt in quite such an appropriate and powerful way. And it gave a lot of creative opportunities to me as director... The Central Office of Information certainly weren’t playing this one safe. In fact, there were those who thought they were embarking on an irresponsible, even foolhardy enterprise.

From the opening sequence, it is immediately evident that they are a far cry from the landscape of the public information films aimed at children that were made upon until this point. A low plane tracking shot across a stagnant swamp, which eventually settles on the figure of the cloaked Spirit shrouded in mist, portentously situates us in a nightmare. A dreamscape of death “eerily redolent of Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now... a distilled horror film, deploying menacing tone and special effects normally the preserve of X-rated cinema shockers” (McGahan). The conventions of a genre designed to frighten adults now repurposed by the state to shock children out of their complacency around water. Yet, the claggy unreality of Lonely Water’s opening is soon placed firmly in the realms of the everyday environment of children and their ‘mucking about’: “As the Spirit tells us, this kind of Hammer horror landscape may seem the ideal site for terror and death, but it is not actually where he is at his most potent” (Burke 193).

Here, the death of the child is a ‘mere instance of humanity’, an indefinite something. Routinely perverted into an event of public occurrence: “Death gets passed off as always something ‘actual’ - namely, as one event among others that will actually happen at some, albeit unpredictable, time and location. But in this, death's character as a possibility gets [un]concealed” (Winch 174). A horror that is situated in Don’t Look Now: “sits in the uncanny valley between these things happen for a reason and these things happen, forcing the viewer to confront humanity’s inability to avoid tragedy despite our desperation to predict the future” (Mecham). Although, in Lonely Water, such pretentious are cut down by the scythe of the Spirit’s wry and unsentimental commentary. Here, adults are told that their children have an amount of agency and autonomy over the dangerous ecologies in which they play. If tragedy befalls them, on their heads be it. Bluntly reaffirming the dreadful reality of parental anxieties surrounding spontaneous specter of the death, a notion which is perhaps most pronounced in the watery environments that surround the children's playscapes.

And for the child viewer: a stark warning that it is their local haunts, not their nightmares, that are haunted by dangerous monsters hiding in plain sight. Ghosts and ghouls are not under the bed but waiting in (un)expected places. The watery places and mundane sites of the everyday, places they transform into fantastical playgrounds. Sites which are desaturated into a monochromatic greyscale of darkened danger.

Shifting from the dreary hellscape of the opening – “The kind of place you’d expect to find me” – our hooded narrator tells us, Lonely Water, the viewer is placed in a quintessentially washed out 1970s locale: a junk-filled building site. The Spirit reminded us that: “But no one expects to find me here, it seems too ordinary”. The situation itself is a timeless scene from childhood, one that anyone who ever had a kick-about with their friends will be overly familiar with – the football has been kicked out of play into an annoyingly hard to recover place. I shudder thinking back to some of the risky retrievals mission myself and my friends undertook time and time again. Climbing spike-topped-fences, rushing across busy roads and wading through fetid water. It is the later situation that the four kids find themselves in this scene, trying to retrieve the ball from a rain-filled hole; a deceptively deep puddle on a partially banked muddy slope. As the young boy attempts to lean over it with a stick and get the football just within reach, the Spirit portentously highlights the precarity of the situation: “That pool is deep, and the boy is showing off... the bank is slippery”. And so, for the forgone tragedy occurs as he slips down into the puddle. Switching to the drowning child’s point of view we can see the hooded figure coming closer to the to the puddle and as he walks over behind his inattentive group of friends who simply do not know what to do to save their friend. The consequentiality of these spontaneous acts of playing around water are wrought large. We see the perished child; the consequence, accidental death by drowning.

This scene is repeated in differing yet all-to-similar scenarios in Grant’s triptych of watery death with “the creepiness here resid[ing] in the film’s construction of a universe that targets children, that lures them to their deaths through the temptations the world offers” (Burke 193). This sense of ‘targeting’ that Burke refers to is elucidating in the three types of children the Spirt ‘picks off’: “the unwary, the show-off, the fool” – all of whom fail to comprehend the hazardous mundanity of every spaces. The second child to drown is the ‘unwary’, who the Spirit tells us are “who are easier still”, dangling on a branch from trying to catch a fish from a pond all on his lonesome – the inevitable happens with the branch unable to hold his weight, snapping he falls into the pond. Indeed, Burke continues in his analysis of Lonely Water, pointing out:

The lesson here is that the greatest danger is not the conventional landscapes of the horror film, but in the most banal sites and spaces... But the terror of the films derives from how it hives childhood inattention and negligence spiritual form and constructs a world view in which children do not simply make errors of judgement or fail to prevent the preventable, but are tracked and targeted by a malevolent force that lays in wait for such moments. (ibid)

The final act of Lonely Water ominously settles on a ‘No Swimming’ sign along a riverbank near an illegal tipping site. Donald Plesance’s voiceover gleefully explains: “Only a fool would ignore this, but there’s one born every minute. Under the water there are traps – old cars, bedsteads, weeds, hidden depths... it is the perfect place for an accident”. Yet, the drowning child is saved by “sensible children” who act quickly using a branch to help their friend out of the water thus neutralizing the Spirit’s power. Nevertheless, the Spirit is unencumbered in his defeat, knowing that it is only a matter of time until he strikes again as he confidently announces, “I’ll be back”, as his cape sinks into the murky water: “the artificial echo of the Spirit’s voice signifies his defeat but also, in a trope drawn from the horror film, heralds his eventual return” (ibid).

Nearly a decade after both Don’t Look Now and Lonely Water, Absent Parents (1982) was a 40-second public information film that was correlative to both. Absent Parents reconfigures the internalized process responsibility of the child’s play around water back on to the parents. It opens with the seemingly innocuous scene, the ambience of children playing in day care. Here a group of children are playing safe and supervised indoors on a climbing structure. But, the composition and tonality of the work quickly transmogrifies into the ghostly familiar landscape of the public information film. In a haunting evocation to the opening scene of Roeg’s film, Absent Parents initially safe depiction of supervised play indoors is quickly juxtaposed with shots of a child playing outside on the edge of a small wooden bridge that crosses a shallow creek.

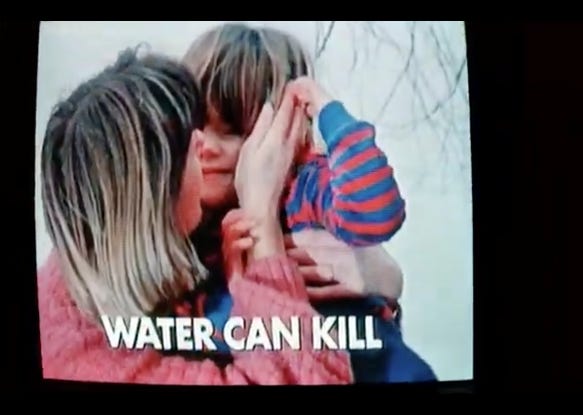

As the female narrators asks the viewer: “Have you ever watch small children at play? In spite of all the rough and tumble they usually come to very little harm. But just imagine them doing all this near water”.

As the ghostly scene simultaneously seeps through the initial frames the sounds of flowing water, splashing footsteps and the disquieting echo of a little girl screaming are meta textually redolent of Don’t Look Now’s familiar opening scene. This cultural recall reminds the viewer of the horror when a child is left to their own device around water. Moreover, although the girl playing by the water is not wearing a red jacket – the bold colour pallet, composition, cinematography and aesthetic sensibility – in the Absent Parents invoke Roeg’s work: “red is the dominant colour and the film exploits the almost spectral pastiness of the children in a manner that emphases their fragility”, Burke continues:

The ghostliness of the children invokes their death despite its prevention and points to the ways in which their parents would be punished and haunted by any lapse in attention, no matter how brief. The message of the film is about the need for constant surveillance and this point is driven home by the weird over enunciation that distinguishes the voice-over: “Never let small children out of your sight if you know they can get near water, however shallow. Children love water, but water can kill”. Once again, the natural world is transformed into a malevolent force or entity that attracts and targets children, luring them to a death that seems calculated rather than accidental. (196).

A double-edged sword then. The danger of water all-invasive with the children and the parents both liable for the slightest (in)action around the element. Yet, wedged in between the haunted horrorscapes of 1973’s Don’t Look Now and Lonely Water and the 1982 Absent Parents were a string of nastier cuts of more graphic content, and therefore harder to stomach public information films aimed at children.

***A drafted excerpt from the 2nd Chapter of my PhD: ‘Scared to Death: Public Information, The Child and Water – please note this this is an unfinished work/project***